The Night the Folk Movement Died

This book is easily the definitive account of Newport ’65 — Elijah Wald explores in depth the various forces that caused that night to go down the way it did.

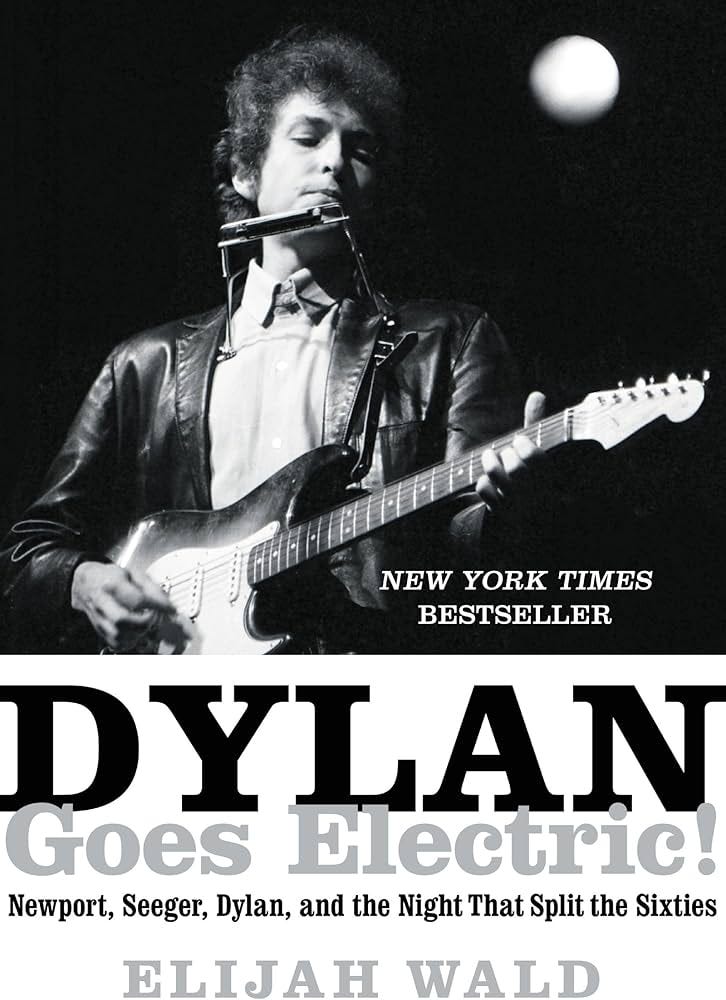

This year (2015) is the 50th Anniversary of Bob Dylan armed with an electric guitar, taking the stage at the Newport Folk Festival, backed by a band organized the night before, with three songs not only disrupted the closing night of the Festival, but blew apart the music scene that had created it. This happened the night of July 25, 1965, a pivotal date in the history of American popular music, that thanks to the Internet would receive far more publicity 40 years after it happened than when it happened. There is every reason to believe that this year the hype will be even greater. One of the fascinating things about that night is that even after all this time no two accounts of what went down are alike, whether those remembrances are from audience members, other performing musicians, members of the press, members of the board of directors of the Newport Folk Festival or other people working at the festival doing sound, as managers, road managers and roadies. More to the point, even the accounts of people who wrote about it when it happened don’t necessarily match up.

Elijah Wald was clearly aware of all this when he decided to devote an entire book (Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night That Split the Sixties) to what was approximately a 35-minute performance. Of course there’s much more to it than that, and what makes this book easily the definitive account of Newport ’65 is that Wald explores in depth the various forces that caused that night to go down the way it did, in a manner that is reminiscent in its research of CP Lee’s account of Dylan’s legendary 1966 Manchester, England concert where an audience member shouted “Judas” in the book Like The Night.

The book starts with a detailed chapter on Pete Seeger that is part biography, but also details how what was eventually called “the folk movement” was pretty much his creation and ultimately filtered through his political worldview. Wald goes into great detail on how Seeger would simplify his banjo and guitar parts because he didn’t want his instrumental prowess to interfere with the message of whatever song he was singing. A good part of the chapter is devoted to The Weavers, the first group to put folk music on the hit parade. The Weavers were often chastised by folk purists for rewriting traditional songs, and one song that was attacked was their hit version of Woody Guthrie’s dust bowl ballad, “So Long, It’s Been Good To Know Yuh” that eliminated all references to the dust bowl. What a lot of people didn’t know at the time and for a long time afterwards was that Guthrie himself rewrote the song for The Weavers and took home a pretty hefty five-figure advance for his efforts.

More fun is that Wald has discovered a never-released single the group recorded for Vanguard Records of the song “Gotta Travel On” with a close to rockabilly arrangement. The Weavers did record “Gotta Travel On” for their final studio album to include Seeger Traveling On With The Weavers. [Seeger, whose offstage persona was nothing like his onstage one quit The Weavers immediately after they recorded a commercial for L&M cigarettes. The group who had been signed by Vanguard following their 1955 reunion concert at Carnegie Hall was in the process of recording their first studio album for the label when Seeger departed. Vanguard, realizing Seeger was a major factor in the group’s appeal, stretched his split over two albums, the first with his replacement Erik Darling as guest artist with more Seeger songs and the second with Seeger as departing artist with more Darling songs. Unfortunately Vanguard has rarely been a company to list recording dates on its albums, so exactly when the split went down is unknown. Wald puts it at 1958, but a biography I have on Lee Hays, the group’s bass singer and leader puts it in 1957.

Wald takes the Seeger introductory chapter up to the beginning of the ’60s. While it is impossible to write about Seeger without writing about his politics, the blacklist, his appearance before HUAC and his trial for Contempt of Congress, Wald manages to keep a good deal of the focus on Seeger’s music.

Wald applies the same approach to Bob Dylan, keeping the focus on the music, and this is where this book differs from most of the other innumerable books on Dylan because Wald sees Dylan as a rock and roller from the start, which in fact he was. He then follows Dylan to Minneapolis, where instead of attending the University of Minnesota, he learned about folk music from various sources discovering Woody Guthrie in the process and eventually makes his way to New York and Greenwich Village. Even when writing about the initial years in New York City, Wald downplays the Guthrie myth, points out that the first few reviews of Dylan were about his musicianship, not his songs, and pointing out that what Dylan was doing was playing folksongs with a wildness that came from rock and roll. It’s a view of Dylan that is refreshing and perceptive.

Wald then presents a history of the Newport Folk Festival, how it evolved from the Newport Jazz Festival, how Albert Grossman who would eventually manage Peter, Paul & Mary, Dylan and many other people was involved from the beginning, how a Board of Directors that would include Seeger, and Theo Bikel among many others was formed, and how Seeger would push the Festival towards his worldview in how the music was presented, what musicians were selected right down to how the musicians were paid.

At the same time Wald connects the folk movement to the Civil Rights movement, and eventually the peace movement, while also delving into a brief but incisive history of the various “commercial” folk groups, most notably the Kingston Trio who arrived in the wake of The Weavers. Also included is a bit about the TV show Hootenanny, which blacklisted Seeger who along with Guthrie came up with the term, and subsequently was boycotted by many artists including Baez and Dylan, but not by a lot of other artists including The New Lost City Ramblers which included Seeger’s half-brother Mike. Wald also takes the time to point out the difference between groups like NCLR who were seriously studying traditional country music and the more collegiate groups who in a lot of ways were singing campfire songs, even if they weren’t campfire songs to begin with.

All of this leads up to the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. Dylan arrived at the festival as a songwriter who was just starting to be known outside of New York City and Boston where there also was a strong folk music scene. Freewheelin’ his second album had only been out a couple of months, Peter, Paul & Mary’s cover of “Blowin’ In The Wind” was hovering around the top of the charts, Pete Seeger was singing his songs all around the country and had recorded them as well, and dozens of other singers were lining up to record his songs. Dylan arrived at Newport a new kid on the block, along with several other new kids on the block including Tom Paxton and Phil Ochs, and left it pretty much a star. Considering there were numerous other musicians also making their Newport debut that summer including Mississippi John Hurt and Doc Watson, it was no small achievement. It was also the year Dylan would play along the most with the Seeger vision of Newport, singing a duet with the man himself at a topical song workshop and closing the festival with a grand finale of “Blowin’ In The Wind” joined by Peter, Paul & Mary, Baez, The Freedom Singers, Seeger and Theo Bikel, which was followed by everyone linking arms for “We Shall Overcome.”

Returning a year later, Dylan was now a star, a far more professional player, but with the exception of the inevitable duet with Joan Baez on “With God On Our Side,” performed no political material preferring what Sing Out! editor Irwin Silber would later refer to as inner-directed probing songs like “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “It Ain’t Me Babe” and “Chimes Of Freedom.” Also of major importance at the Festival that year was a country artist named Johnny Cash, who made the connection between country and folk and always had an eye on the folk scene.

It should be pointed out that in those pre-Monterey and pre-Woodstock years, Newport was the festival. It presented an astounding array of musicians from city blues to country blues, from old time fiddlers to gospel singers to Irish and English balladeers to Cajun and Zydeco acts that few knew about to white and black gospel music to almost forgotten traditional singers. This diverse lineup was imitated but rarely equaled at similar festivals. On top of this Newport had a camaraderie between both the musicians and the audience that made it special.

Wald deftly uses all these elements to build up to Newport ’65, a year with another stellar lineup, but also where a lot of strange things happened from Richard and Mimi Farina making their debut playing in a downpour, to the emergence of Donovan, to the legendary fistfight between Alan Lomax and Albert Grossman over Lomax’s insulting introduction of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Dylan as he had the other two years played what was now called the “Contemporary Songs Workshop,” debuting an acoustic version of “Tombstone Blues” and drawing so many people to the workshop that their presence and their reluctance to let Dylan leave after a short set interfered with the other workshops taking place at the same time.

Wald details what went down at the rehearsal off festival grounds that night of Dylan, the Butterfield rhythm section, their brand new guitarist Mike Bloomfield, and keyboard players Al Kooper and Barry Goldberg. He goes into equal detail about the sound check the next afternoon, some of which can be seen in the documentary about Newport, Festival by Murray Lerner with a lot of new details from various people who were assisting during the sound check.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Joker and the Thief — Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.