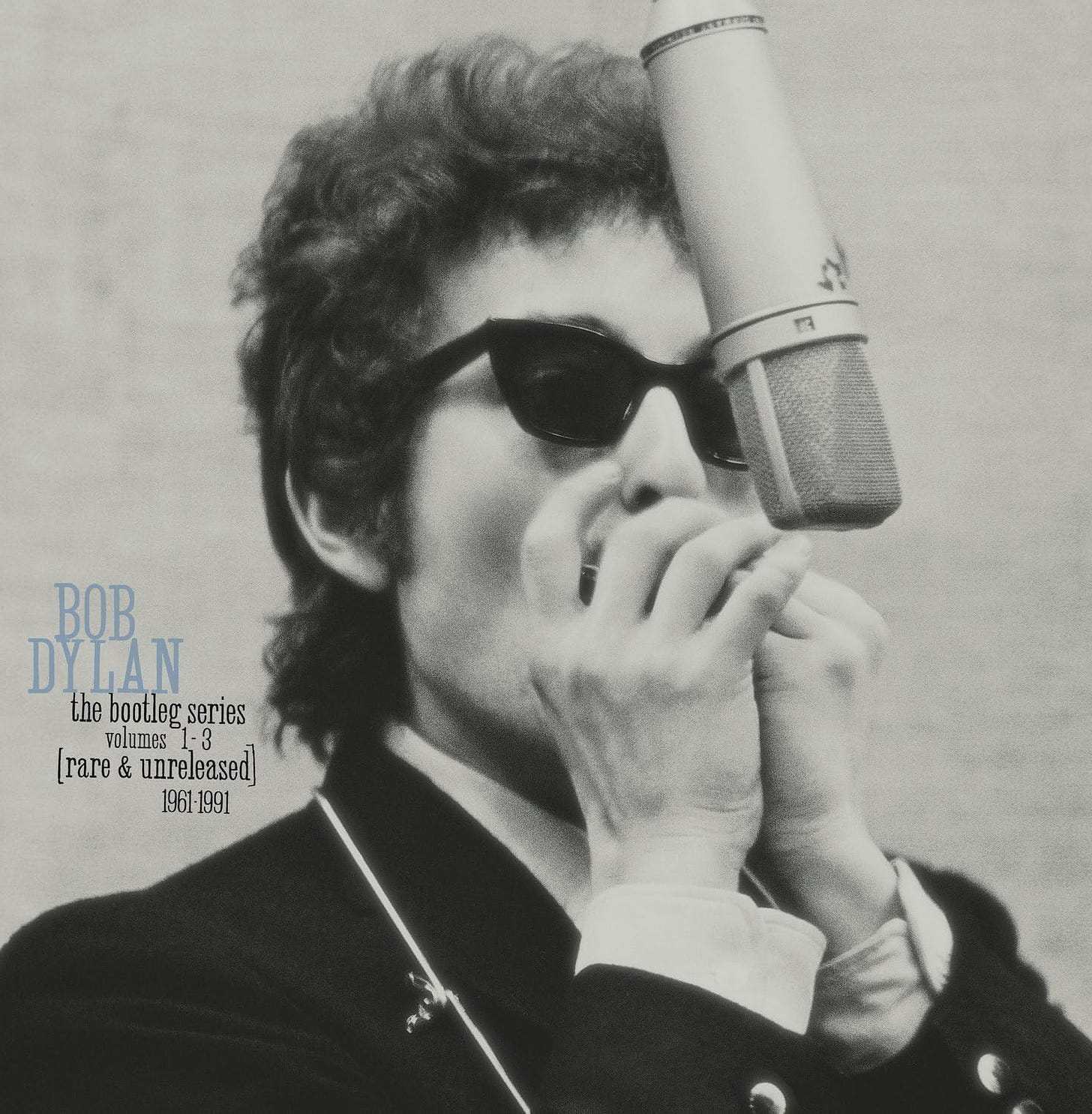

The Bootleg Series, Volumes 1 -3 (Columbia)

For more than two decades, an international underground network of Dylan fans has bought, sought and traded bootleg Dylan tapes and records.. (The Bootleg Series Vol 1-3)

Written at the time of release.

With 58 previously unreleased tracks filling three CDs to capacity, one would think the new Bob Dylan box set, The Bootleg Series, Volumes 1 -3 (Columbia), would close the gaps in his catalogue. But it’s only the beginning.

For more than two decades, an international underground network of Dylan fans has bought, sought and traded bootleg Dylan tapes and records.. To their fascination and frustration, these collectors discovered long ago that these tapes – culled from alternates and outtakes, publishing demos, live performances and rehearsals (while of dubious sound quality) – often turn out to be as good as and sometimes better than the official releases.

This collection is chronologically arranged, spanning 1961 to ’89; half the songs were recorded before Dylan went electric in 1965. Still, the set touches on almost every phase of his career.

Some critics are questioning the motives behind this release, but it goes a long way toward getting some of Dylan’s greatest songs and performances out, with sound quality that isn’t tenth generation. In fact, the sound throughout is high quality.

Dylan’s ‘60s concerts served as vehicles to try new songs, and you waited for the next album to hear them again (the opposite of the music scene today, when concerts often function as advertisements for an act’s latest record).

Many of the songs here were staples of those shows, such as the anti-boxing ‘Who Killed Davey Moore?’ ‘Walls of Redwing’ and ‘Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,’ which lampoons the extremist organization that carried McCarthyism into the ‘60s. Dylan walked off the Ed Sullivan Show when they wouldn’t let him sing it; thene Columbia (fearing a lawsuit) deleted the same song from Freewheelin’ ‘Let Me Die in My Footsteps’ also deleted from that album in favour of ‘Hard Rain,’ was an eloquent response to the bomb-shelter craze of the early ‘60s, revealing Woody Guthrie’s influence more than any other Dylan song with lines like, “Let me drink from the waters where the mountain streams flood/Let the smell of wildflowers flow free through my blood.”

The inclusion of several folk songs shows how this music shaped and defined Dylan’s art. Two early original narrative ballads – the rollicking ‘Rambling Gambling Willie’ and the sombre ‘Seven Curses’ – deal with familiar Dylan moralistic themes: the outlaw as hero and the hypocrisy of justice.

These songs fit firmly into the folk tradition. Strangely, no Guthrie songs are included though his spirit dominates the three talking blues. Like Guthrie, Dylan often used traditional melodies for his songs.

Dylan’s penchant for mixing musical genres started early. The Childe Ballad, ‘House Carpenter,’ is sung like a blues, while the reeling and rocking ‘Quit Your Low Down Ways’ – a reworking of Kokomo Arnold’s ‘Milk Cow Blues’ – reflects Elvis Presley’s influence.

Among the traditional songs, the haunting ‘Moonshiner’ is one of Dylan’s greatest performances. Emotionally sung to soft finger-picked guitar, it gets into your soul and stands as the definitive example of how to sing a folk song.

The original ‘Eternal Circles’ is a song within a song about a performer watching a girl watching him, wanting to meet her but having to finish the song. The girl vanishes at its conclusion.

‘Mama, You Been on My Mind’ is both country and poetic, with cascades of words similar to ‘Tambourine Man.’ This version is slow, careful and sad, proving author Betsy Bowden’s point (in her scholarly Dylan book, Performed Literature) that he defines a song by how he sings it, giving it different meanings at different times. In concert, he usually sang it in an exuberant buoyant fashion.

‘Farewell Angelina,’ recorded first by Baez, is presented here by Dylan for the first time. One of his most poetic songs, it shows the beginnings of the obscure, impressionistic imagery that would dominate his mid-‘60s work. Written on several levels -as a farewell to a lover or a period in life, or as a subtle anti-war songs – the lyrics are not quite perfected. Still, it’s one of the high points.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Peter Stone Brown Archives Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.