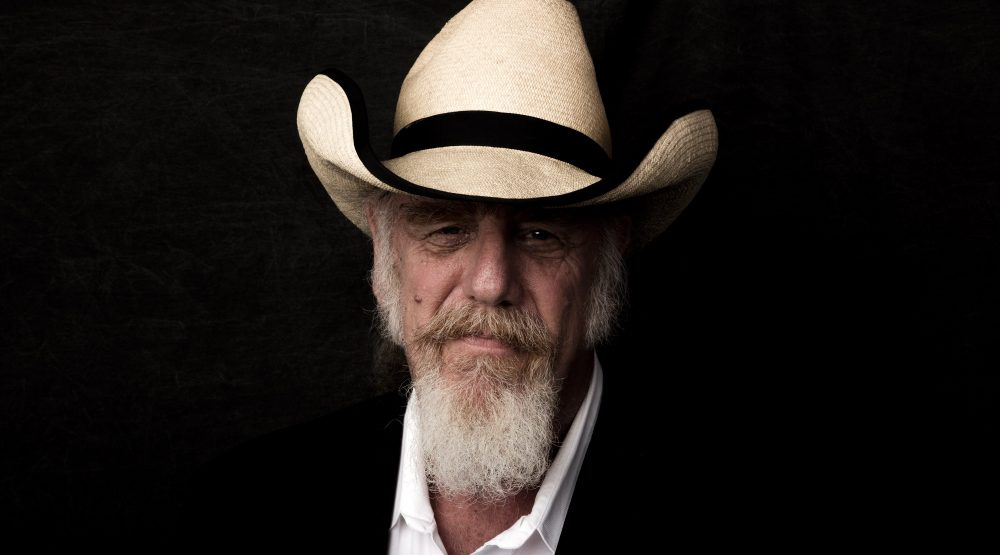

Interview with Ray Benson of Asleep At The Wheel

How old were you when you started playing?

Nine years old. I picked up the guitar when I was nine.

And you played the Robin Hood Dell when you were ten or 11?

I guess it would be ten, almost 11, yeah ten years old.

In the liner notes you say you wrote these songs over a ten year period, was this a conscious effort to take your music in a different direction?

No man, you know it was sort of like you know the deal, you’re just sitting there writing and this is what came out. So it was just that creative process.

Was there a point when you realized you had enough material for an album and it was going to be something different?

Well, it started with the song “A Little Piece,” and that was like a six-year journey. I started it and Michelle said, “You gotta finish this song, it’s really amazing.” I went okay. And so what I did was basically you know just took my three-foot high stack of scribblings and then went back through it and wrote some new ones, and then found half finished ones and finished them and realized I had a shit load of material here that I sort of put on the side burner, and knowing that it was going to go an Asleep At The Wheel album. So I had all these partially finished or finished songs, and that was the process.

When you were writing did you hear the arrangements and instrumentation in your head or did that come later?

That’s later, much later. And that was part of getting Lloyd Maines ’cause I knew – I felt the material was – Lloyd and I, we’ve produced some records together. We did those James Mann records. We’ve worked together quite a bit over the years and I knew that he would be the guy, not only to help with the arrangements, but to play it. In the studio, it all took shape.

It seems to me in a lot of ways to be the most personal album you’ve made.

Yeah, yeah, because when I write swing music, and western swing music and boogie, and that sort of thing, it’s really writing to a form, you know. And this was the songs that come out and you’re just sitting on your ass, and of course, it’s very personal.

In a certain sense, while you’re trying a lot of different styles, you’re not straying all that far from country.

Well, yeah, I don’t know, that’s just sort of what came out, although it was funny, sort of they went in spurts. There was the stuff. And then it got weirder with the J.J. Cale song. But there was no conscious effort. You know, same thing. Any music that enters my head, if I can get away with it, let’s do it.

When did you write “J.J. Cale?”

I wrote that after I was finished (the album). It was right after Cale died. I called him up about a month before he died. But that was the last song I wrote. I wrote that after we had finished recording most of the stuff.

What struck me about it was it’s also a tribute musically.

Yeah, thank you. I’m glad you noticed. You know I just loved Cale man. I’d get to see him about every other year, every three years, somewhere back you know in the day or on the road. He just seemed like such a kindred soul. We would talk about the same things. I just loved him. When I did that Carolyn Wonderland record, he sent me a couple of, three songs, and we did one of ’em. He was a master. He was just great, a master, and I just wanted it to sound like Cale’s records.

It shows to me a whole other side of your guitar playing that you don’t get to do with The Wheel.

Yeah, that’s the whole deal. That was the other thing, I wanted to show people, hey, I took 50 years learnin’ this son of a bitch (laughs), And I can play. So anyway, it was great. I just played it for Delbert McClinton yesterday, and he loved it.

Who are those guys on “Heartache and Pain?” I never heard guitar – it’s not quite flamenco.

Oh yeah, they’re called the del Castillo Brothers. It’s flamenco rock. It’s just these two guys, they’re in town. I produced a record on them of them and Willie Nelson doing “I Never Cared For You.” And they’re you know, that’s what it is, I had written a song that was very angry, flamenco, and I just started playing it. I play the intro lick you know and I could’ve played, but I went no man, they’re good friends of mine and this is just right up their alley. Yeah, Mark and Rick, the del Castillo Brothers, they’re just, they have a band called Del Castillo and that’s what they do.

There’s a lot of amazing guitar on the record.

Yeah, that was the idea. I played all of the guitars, and the way we cut it was me and Lloyd and Evan Arrendondo and David Sanger on drums, and either Chris Gage or Floyd Domino on piano, and we just cut those basics and then overdubbed what we wanted. I just wanted it to be different from an Asleep At The Wheel album.

It’s one of those records where even on the tenth listen, I’d heard something and go reaching for the cover to see who was playing.

Well good, ’cause we’ve got a great bunch. In the last five or six years the town has really made it.

Speaking of Floyd Domino, one of the tracks I really love is “In The Blink Of An Eye.

Yeah, thanks man. That was just one of them things you know. The melody came out and I had been fucking around with that melody and if you’re trying to write a standard, it’s really tough because you’re up against Hoagy Carmichael and the Gershwins and everything. And I finally said, wow, I got this melody and then it was just I had just broken up with Michelle, and it was one of those things that all of a sudden I get a phone call and a six year relationship’s over. It was like whoa, that shit just happens in the blink of an eye, I said, oh man, there you go.

Is there any one songwriter you would say is your greatest influence or inspiration?

No, I think all of them, you know. A friend said, when I’m writing, I gotta stay away from Dylan ’cause all of a sudden you start trying to write like Dylan. No, that’s Bob, don’t even go there. Do I love ’em all? Oh yeah, sure. Guy Clark is my favorite I think. John Prine and Guy Clark are two that just killed me, Billy Joe Shaver. I really just have to shy away from that ’cause I really just have to write like me. And I’m so different because my influences are so wide.

The other thing I want you to know is just there’s the finger picking. You know they tell the story about the Coen Brothers movie, about how they had to teach the actor how to finger pick, and how difficult it was. I said yeah man, that style of playing is, I don’t know how to describe it except that it ain’t easy to learn how to do and then to apply it to a creative process.

So anyway, I love ’em all, everything from Irving Berlin to Dylan to Willie Nelson. I take ’em all in.

Tell me about the Waylon song. Who’s the co-writer on that?

Yeah, Gary Nicholson. Gary’s written a bunch of hits for everybody from Kenny Chesney to George Strait and a lot of Delbert McClinton stuff. And he’s a great, great guy. He’s a Fort Worth guy, and a great guitar player too. He plays in Delbert’s band and he’s written with everybody in Nashville. He’s had some really big hits. But he’s and R&B guy. Anyway, he and Waylon wrote the song a couple of years before Waylon died, and it was sent to Sam, my kid for another project like four years ago. And we almost finished the album, and Sam said, “You need some other song.” That’s when we got the J.J. Cale thing in, and he said, “Check this out, I forgot about this.” It was on a cassette, just Waylon singing with a guitar. And I went, oh shit, that’s incredible. We toured with Waylon. I knew him very well. You know the first time I heard Waylon was in Philly. Anyway, it was his first album on A&M, I think it was called Rock Salt & Nails or something like that. So anyway, I loved Waylon, I got to know him, toured with him a lot and everything. So he recorded it, and I was listening back to it, and I said, Willie’s gotta do this with me. He’s just gotta do it, so I called him up and we went out and did it. And Gary told me, he started the song and then Waylon finished it. When I told him that I’d done it with Willie, he like almost cried. He said, “Ray, you don’t understand, that whole thing, that whole idea for the song I got was from one of Willie’s autobiographies. He says, I look in that mirror and I see this old guy with wrinkled skin, and I go that’s not me. That ain’t me.” That’s where Gary got the idea to write the song.

I thought Willie’s vocal on it was chilling.

What can I say? We went out to the western down there and brought some equipment, it wasn’t even a studio. We brought some of our equipment, Sam and Steve and some of our engineer friends, and sat around and smoked four joints. It was so funny ’cause I played him the song, and the melody and he went, “You mind if I just sing?” I said, “No man.” He said, “Waylon always told me, I didn’t have to sing the melody, just make up my own.”

How many miles do you think you’ve traveled in your 43 years on the road?

Well, we figured it out the other day. It’s somewhere between two and a half to three million miles.

As you know, in the past few years, we’ve lost a lot of the great ones in country music, most recently Ray Price, well most recently Phil Everly. Do you see anybody coming along who’s gonna pick that up?

Well, talent-wise they’re all over the place. Everything from Buddy Miller to Jim Lauderdale to I can’t remember some of the guy’s names. Anyway, there’s wonderful music all over the place. It’s just not on country radio. So the mainstream radio in all genres are just pitiful. So the music’s being made, but it’s not being played on mainstream radio. So I hear a lot of, you know XM, Sirius, the Outlaw Channel, Willie Channel, etc., has great music. But there’s also a lot of horrible music both of the independent variety and of the mainstream variety. So it’s kind of funny how that is, but no, there’s great music. And even in mainstream, like I saw Kacey Musgraves the other day. She’s wonderful you know. Will it ever be like it was? Hell no. I mean are you gonna see guys with 60 year careers, like Ray Price, like George Jones, Willie Nelson. I don’t think so. I think the economics are such that they don’t have to, there’s no incentive for people to create great music that’s commercial. You know what I mean? So there’s no incentive, there’s nothing there that lives you know. But I think everything goes in cycles. Is there talent? Absolutely yes. And down here you know – in fact have you seen my TV show?

No, I haven’t.

It’s on youtube, The Texas Music Scene with Ray Benson. I’ve been doing it for four years now and we do all of these Texas acts. We’re on ii four or five cities down here, a Saturday afternoon country music show. Basically you know I’m replacing Porter Wagoner. But it’s just in Texas, Oklahoma, and we’re just now getting on, we’re in Nashville, and some sub stations, some cable stuff and whatnot. But it’s all over youtube. We post all of our shows on youtube. But there’s lots of great talent, and luckily here in Texas, we’ve got it now. It’s never gonna be the same music but still there’s some great soulful things, like creating and writing great songs. Well, Hayes Carll’s great. Hayes is wonderful. He’s not the greatest singer, but he’s a great songwriter, an amazing songwriter. There’s lots of cool bands down here, the Dirty River Boys, they’re from El Paso. All young guys, these are all 20, 30 something guys. Stoney LaRue, he’s got like a country rock band. But really good. And of course Bruce Robison and Kelly Willis do incredible stuff. Charlie Robertson’s still making great records. Really cool stuff. It’s just there. It’s just not gonna be played on your radio where everybody gets to hear it which is sad.

It seems like youtube is one of the great conduits for finding out about music these days.

Oh yeah, those guys over at Sony Records, they just, they got seven interns sitting there working for nothing watching youtube and telling them what’s interesting. And fine, people will find the music and there will be good music and bad music. It’s always been like that. The sad part is the fiscal part, the money part. But again before that the record companies were screwing you. So some things never change.

Right. Well, you told me last time I saw you, “no more record companies for me.

No, we started our own and we’re doing great man. We just signed another guy, this guy Eric Burns. We’ve got all kinds of music and we’ll do it, and we know just enough to not lose money doing it. We’re not making any money, although we did on Willie and The Wheel, but that was Willie, you know. We’ll be putting out the next Bob Wills Tribute album. We’re almost done. We’ve got George Strait, Vince Gill, Willie Nelson, Robert Earl Keen, Buddy Miller, Jamey Johson, the Avett Brothers are gonna do a cut, Lyle Lovett’s gonna do a cut, Terry Rodriquez did one, Chad Edmonson. We're gonna make a go of it. I’m trying to raise some money so that I can sign some of these guys and do ’em right. And we’ll see what happens.

Do you have any advice for the songwriters out there?

Yeah, don’t quit. Stay out of jail and don’t quit. The main thing is figure out what kind of songwriter you want to be. You want to write songs for yourself? That’s great. You can do anything you want. If you want to write songs for others, then you’ve got to go to one of the music centers, Nashville, New York, LA, and find publishers if you want to write songs for other people. A lot of that’s about networking and hanging out. So that’s my advice. If you want to write for yourself, do whatever the hell you want. But trying to do that other one is more of a business. And you’ve gotta go down and network with the publishers, with the producers. And they’re in Nashville mostly. There’s still some in New York, some in LA, and a little bit in Austin. But writing for other people, you’ve gotta have partners, publishers and producers.

I’ve heard a lot of the songwriters in Nashville they’ll write with this guy at 11 am and that guy at 2.

Oh that’s what I mean, that’s the way it always is. You’re in the middle of that, oh I’ve gotta go, I’ve got another appointment, oh see ya. Harlan Howard was the first guy. He would get up every morning and go into the office and from nine o’clock to two o’clock, he’d write songs. And sometimes he’d co-write, but mostly he’d write. And then he’d go out and get drunk the rest of the day. So the whole, that’s the discipline of writing for others. Actually my best advice to other songwriters, if you write 1,000 songs, they can’t all suck.