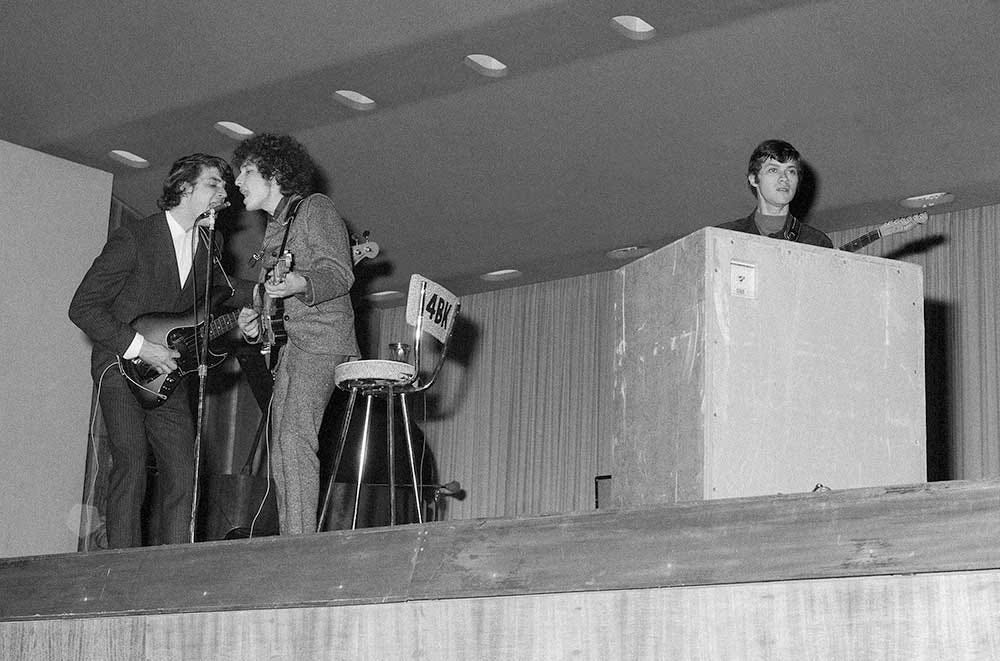

Bob Dylan with Bob Fass sometime after midnight

I ran into my brother’s room and said, “Get up! Dylan’s on BAI.”

It was sometime after midnight in the early hours of January 26, 1966 when I fell asleep, as I usually did on week nights: listening to a show on New York’s WBAI FM called Radio Unnameable, hosted by Bob Fass. I woke up an hour or two later and, in the first few seconds of consciousness, realized that Bob Dylan was on the air, in the studio, and taking phone calls. Let’s just say I woke up really fast, and found myself with a quick decision to make: whether or not to wake up my older brother who was sleeping in the next room.

I was 14 years old and in 9th grade. It was the worst possible night for this to happen - right in the middle of a weeklong nightmare known as midyear exams, and I was supposed to take a math exam (the worst) only a few hours later. I decided that exams come and go, but Bob Dylan at the height of his rock and roll stardom taking phone calls on the air was a one-time-only event. So I ran into my brother’s room and said, “Get up! Dylan’s on BAI.”

Bob Dylan: Did you n…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Joker and the Thief — Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.