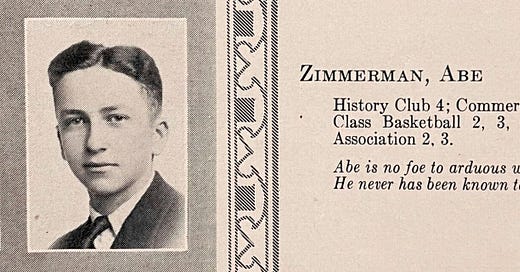

Abe Zimmerman talks Bob's early years and road to fame

Abe Zimmerman in his own words: sourced from Robert Shelton's May 1968 Interview with Abe and Beatty in Hibbing.

It's hard to anticipate Bobby – he might say, “Oh, I don't care,'' but on the other hand, I know that way deep he does care.

Shelton: Do you think Bob will come back to Hibbing?

Abram: - Long pause, no answer.

Shelton note: The irony of this is that three weeks later the father died and Bob came back, reluctantly, for his funeral.

Shelton: Do you think he will come back to Hibbing one day, or don't you know?

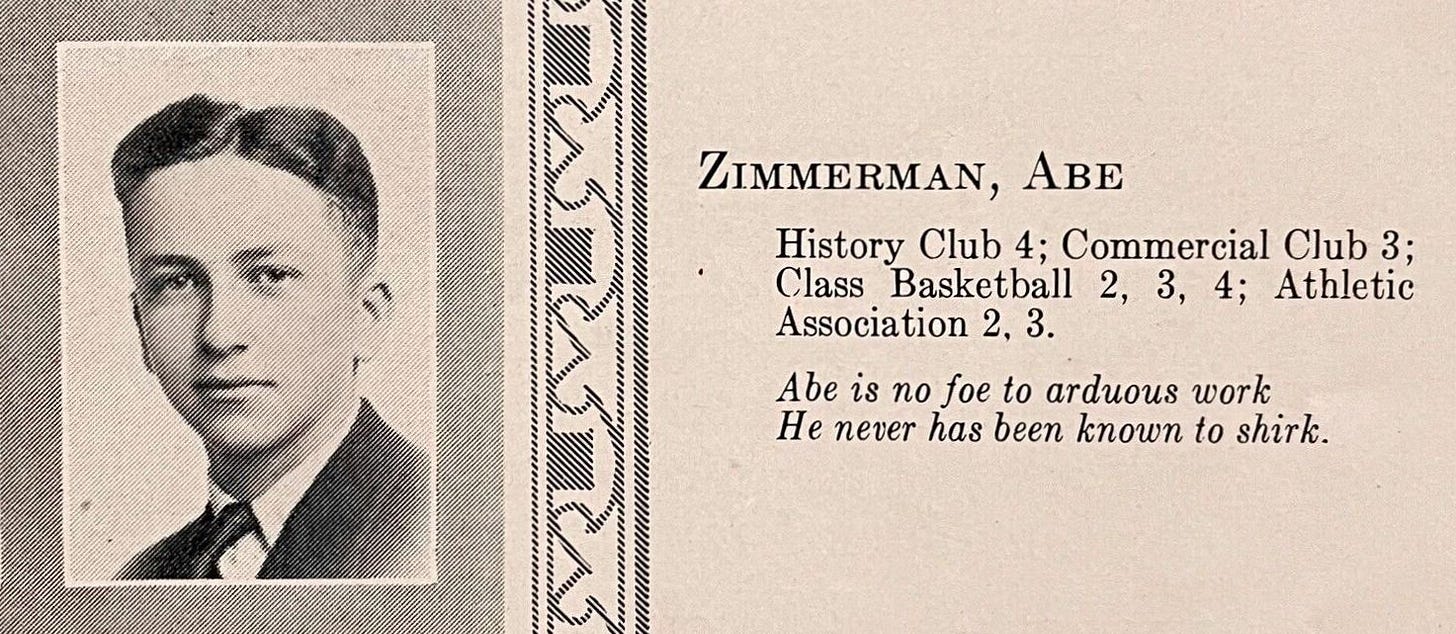

Abram: - Continues to look at picture and ignore my question. Here is a picture of him in August 1954 at the Theodore Herzel Camp, outside of Webster, Wisconsin.

I was born in Duluth, in 1911. I went to school there. In those days, you were just required to pass, which everybody did. We were all from immigrant parents, everybody worked when they were seven years old – you sold papers or shone shoes, because that was the thing that was done, and you didn't know of anyone who wasn't doing anything like this. All your friends were doing this. Then you grew up, and tried to play ball, athle…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Joker and the Thief — Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.